Organic Mess

text by Alex Bacon, New York 2014

In a digital age premised on the omnipresence—or, more precisely, the saturation—of mediated forms of experience, materials, stripped down, isolated, and presented as such, have a renewed potential to make a significant impact. This situation informs Manor Grunewald’s Organic Mess series of ten 150 x 200 cm paintings. Today abstract painting in particular has taken on a new relevance, not only for its ability to establish a material presence, but also because its inherently visual orientation has taken on new meanings in the context of the digital screens through which we are now used to receiving visual information.

Because a painting can today suggest both this screen space, and also the kinds of illusory pictorial space that have historically been constructed there, everything placed within a given painting’s literal boundaries is put into question as an image one or more times removed from the realm of actual existence. This is true even if, as in the case of Grunewald’s paintings, what is to be found there is the subtle and complex result of a carefully considered materialist practice. For, even if we spend much of our time engrossed by various screens, this just means that when we happen to look up and encounter something in the actual world we have a renewed curiosity about its particular physicality, and the means by which it came into existence, whether naturally or industrially, something that extends to, and characterizes Grunewald’s series of Organic Mess paintings.

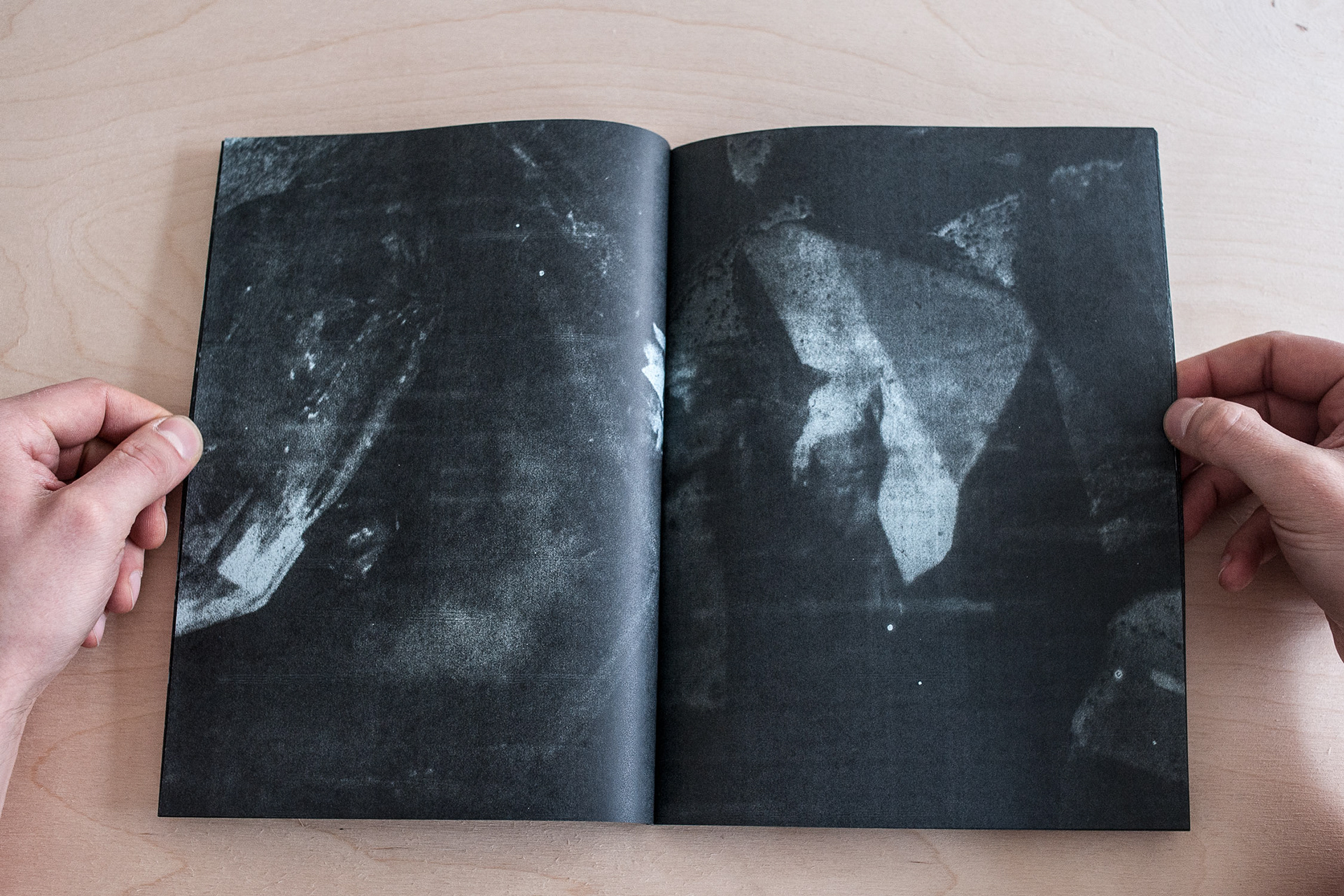

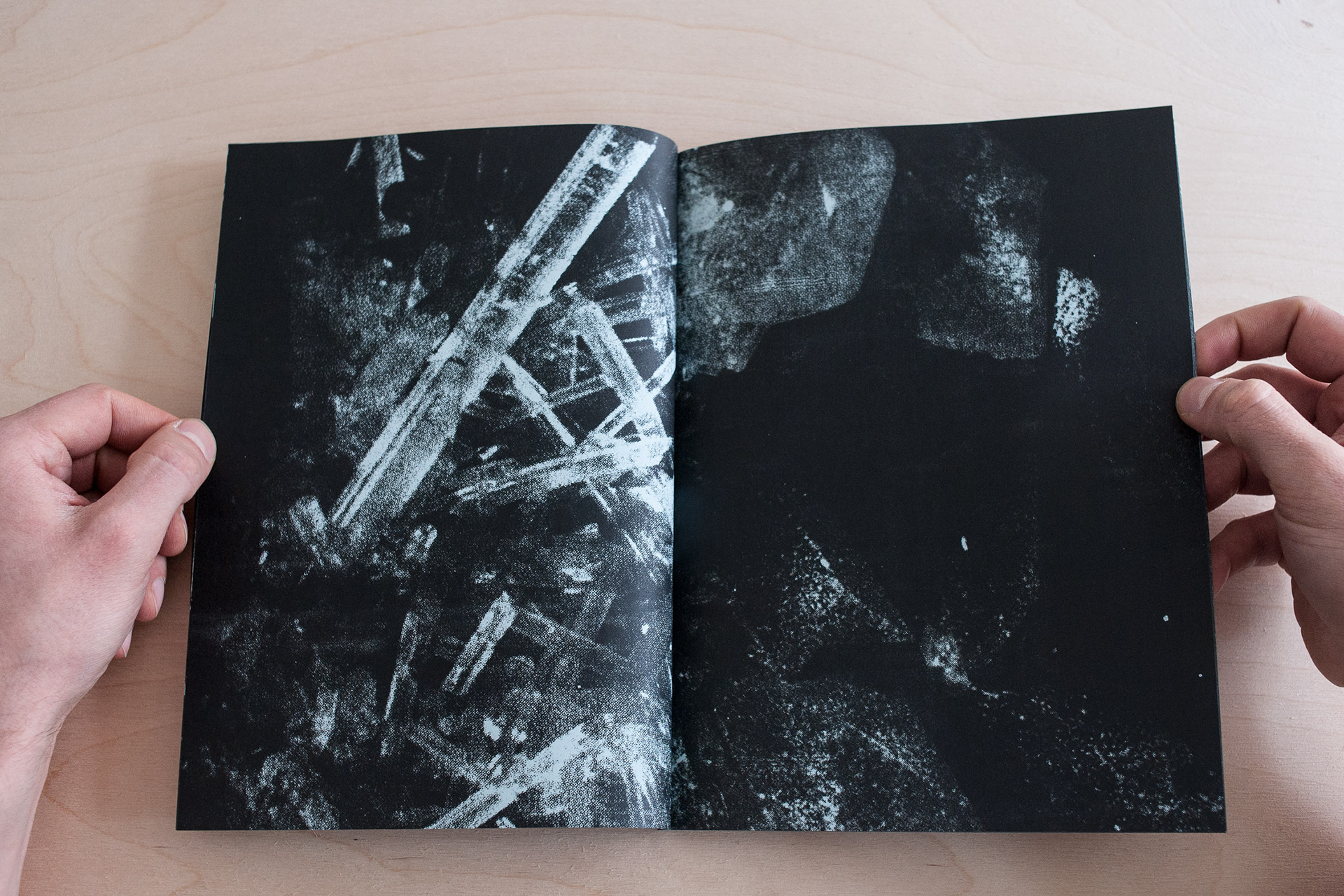

Having observed the way paint looks on the plastic he lays down on the studio floor while he works on paintings on the wall, Grunewald arrived at this body of work by thinking to lay out approximately ten by ten meter lengths of this plastic, and silkscreen onto it close ups from a book of photographs of minerals. He printed layer upon layer, one on top of the other, with no intention of perfectly reproducing this source material. After screenprinting several layers onto the plastic, to the point at which a certain pictorial depth had been achieved, Grunewald would step back and judge which section of the resulting image to crop out and stretch around an unmarked, white canvas. This process is not unrelated to how cropping and layering works in programs such as Illustrator and Photoshop. However, unlike the typical ends to which such programs are used—to achieve greater clarity and “perfection” in an image by reducing and eliminating perceived errors, distractions, and imperfections—Grunewald seeks a certain density of field, which becomes almost unreproducible in its subtle variations amongst layered passages of black.

After cutting out a selected segment of printed plastic, Grunewald wraps it around a blank canvas support and then uses a spray gun to add a coat of shiny black lacquer. This final layer is applied in an all-over fashion, but unevenly, such that it covers certain areas more than others. Parts of the painting are thus a mute, dense black, while others open up to reveal a certain kind of depth, which in some cases is literal, as, for example, when the white of the raw canvas shows through from underneath the plastic. While in others the sense of depth has a more ambiguous pictorial quality, as what at first seemed to be simply uninterrupted black opens up to reveal different tones and forms ghosting just below the surface.

This is not unlike the dense, complex layers that Jasper Johns achieves in his encaustic paintings, where depth is also both literal, in the build up of wax and oil brushstrokes, and optical, in the effects this layering creates in the eye. Also like Johns, as well as Brice Marden, Grunewald allows his activity to peter out around the work’s edges, such that the sides of a given Organic Mess painting reveal traces of the means that produced the work in question. There we see more clearly the different silkscreened layers, as well as the underlying canvas support.

It must also be said that Grunewald’s Organic Mess paintings are architectural in both their address to the viewer, and their activation of his or her body as it circulates in the room with the paintings, as well as in terms of the work’s relationship to the space in which it is installed. Each canvas appears, large, dark, and object-like, and, as such, one cannot help but see it in relation to the wall on which it is hung, the spacing of one work from the next, as well as feel the overall emotional tone the works establish based on their relation to the scale of the room in which they are shown, and to that of the bodies that behold them. This tone can be felt to darken when, walking around the room and viewing the works from various angles, one inevitably notes that the plastic surface, though generally mute and obdurate, from certain vantages catches the light, which ripples over the tautly stretched material, causing the viewer to experience that surface as a kind of skin, especially as light gets caught, flashing amongst the puckers and pulls the plastic takes on in the act of being stretched around the canvas.

Grunewald has chosen to use shiny rather than matte black in these paintings so as to heighten this environmental valence. However, it should also be noted that this architectural reading of the works is complicated by the fact that, while one initially perceives a unity between what, at first glance seems to be a sequence of ten identical black panels, and which thus turn the viewer out towards the space in which the works are presented, closer inspection shows that each work is in fact subtly different from the others, such that, over time, the astute viewer finds a more and more nuanced experienced premised equally on the similarities and differences between each work, and between all the works taken as a discrete series.

Grunewald’s Organic Mess series incorporates materials that are both traditional to painting—such as paint and stretched canvas—and those which are non-conventional, especially the plastic with which Grunewald wraps the canvas. The result is a work that both speaks with the weight of painting’s long and heady history, and reinvigorates it with new materials that open out the scope of the work’s address by incorporating aspects of the labor of making, which is to say the “organic mess” that gives rise to much of the best art. In Grunewald’s hands painting, as such, is thus neither debased, nor elevated, but is rather used as a vehicle or tool to generate a timely aesthetic experience, one where we are made aware of materials and how we newly perceive them in a digital age. He then goes a step further to make intuitive use of this condition with works that interact with both the architecture of the site of display and activate the body of the viewer that beholds them.